library(nlme)

kiwishade <- DAAG::kiwishade

kiwishade$plot <- factor(paste(kiwishade$block, kiwishade$shade,

sep="."))

kiwishade.lme <- lme(yield~shade,random=~1|block/plot, data=kiwishade)

summary(kiwishade.lme)

Linear mixed-effects model fit by REML

Data: kiwishade

AIC BIC logLik

265.9663 278.4556 -125.9831

Random effects:

Formula: ~1 | block

(Intercept)

StdDev: 2.019373

Formula: ~1 | plot %in% block

(Intercept) Residual

StdDev: 1.478623 3.490381

Fixed effects: yield ~ shade

Value Std.Error DF t-value p-value

(Intercept) 100.20250 1.761617 36 56.88098 0.0000

shadeAug2Dec 3.03083 1.867621 6 1.62283 0.1558

shadeDec2Feb -10.28167 1.867621 6 -5.50522 0.0015

shadeFeb2May -7.42833 1.867621 6 -3.97743 0.0073

Correlation:

(Intr) shdA2D shdD2F

shadeAug2Dec -0.53

shadeDec2Feb -0.53 0.50

shadeFeb2May -0.53 0.50 0.50

Standardized Within-Group Residuals:

Min Q1 Med Q3 Max

-2.41538976 -0.59814252 -0.06899575 0.78046182 1.58909233

Number of Observations: 48

Number of Groups:

block plot %in% block

3 12

anova(kiwishade.lme)

numDF denDF F-value p-value

(Intercept) 1 36 5190.560 <.0001

shade 3 6 22.211 0.0012

intervals(kiwishade.lme)

Approximate 95% confidence intervals

Fixed effects:

lower est. upper

(Intercept) 96.629775 100.202500 103.775225

shadeAug2Dec -1.539072 3.030833 7.600738

shadeDec2Feb -14.851572 -10.281667 -5.711762

shadeFeb2May -11.998238 -7.428333 -2.858428

Random Effects:

Level: block

lower est. upper

sd((Intercept)) 0.5475859 2.019373 7.446993

Level: plot

lower est. upper

sd((Intercept)) 0.3700762 1.478623 5.907772

Within-group standard error:

lower est. upper

2.770652 3.490381 4.397072 8 Multi-Level Models and Repeated Measures Models

Models have both a fixed effects structure and an error structure. For example, in an inter-laboratory comparison there may be variation between laboratories, between observers within laboratories, and between multiple determinations made by the same observer on different samples. If we treat laboratories and observers as random, the only fixed effect is the mean.

The functions lme() and nlme(), from the Pinheiro and Bates nlme package, handle models in which a repeated measures error structure is superimposed on a linear (lme4()) or non-linear (nlme()) model. The lme() function is broadly comparable to Proc Mixed in the widely used SAS statistical package. The function lme() has associated with it important abilities for diagnostic checking and other insight.

There is a strong link between a wide class of repeated measures models and time series models. In the time series context there is usually just one realization of the series, which may however be observed at a large number of time points. In the repeated measures context there may be a large number of realizations of a series that is typically quite short.

8.1 Multi-level models – examples

The Kiwifruit Shading Data, Again

Refer back to Section 3.8 for details of the data. The fixed effects are block and treatment (shade). The random effects are block (though making block a random effect is optional, for purposes of comparing treatments), plot within block, and units within each block/plot combination. Here is the analysis:

We are interested in the three sd estimates. By squaring the standard deviations and converting them to variances we get the information in the following table:

| Variance component | Notes | |

|---|---|---|

| block | 2.0192\(^2\) = 4.076 | Three blocks |

| plot | 1.4792\(^2\) = 2.186 | 4 plots per block |

| residual (within group) | 3.4902\(^2\)=12.180 | 4 vines (subplots) per plot |

The above gives the information for an analysis of variance table. We have:

| Variance component | Mean square for anova table | d.f. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| block | 4.076 | 12.180 + 4 \(\times\) 2.186 + 16 \(\times\) 4.076 = 86.14 | 2 (3-1) |

| plot | 2.186 | 12.180 + 4 \(\times\) 2.186 = 20.92 | 6 (3-1)\(\times\)(4-1) |

| residual (within gp) | 12.180 | 12.18 | 3 \(\times\) 4 \(\times\) (4-1) |

Now see where these same pieces of information appeared in the analysis of variance table of Section 3.8:

kiwishade.aov<-aov(yield~block+shade+Error(block:shade),data=kiwishade)

Warning in aov(yield ~ block + shade + Error(block:shade), data = kiwishade):

Error() model is singular

summary(kiwishade.aov)

Error: block:shade

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

block 2 172.3 86.2 4.118 0.07488

shade 3 1394.5 464.8 22.211 0.00119

Residuals 6 125.6 20.9

Error: Within

Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

Residuals 36 438.6 12.18 The Tinting of Car Windows

In Section 2.6 we encountered data from an experiment that aimed to model the effects of the tinting of car windows on visual performance . The authors are mainly interested in effects on side window vision, and hence in visual recognition tasks that would be performed when looking through side windows. Data are in the data frame tinting. In this data frame, csoa (critical stimulus onset asynchrony, i.e. the time in milliseconds required to recognise an alphanumeric target), it (inspection time, i.e. the time required for a simple discrimination task) and age are variables, while tint (3 levels) and target (2 levels) are ordered factors. The variable sex is coded 1 for males and 2 for females, while the variable agegp is coded 1 for young people (all in their early 20s) and 2 for older participants (all in the early 70s).

We have two levels of variation – within individuals (who were each tested on each combination of tint and target), and between individuals. So we need to specify id (identifying the individual) as a random effect. Plots such as we examined in Section 2.6 make it clear that, to get variances that are approximately homogeneous, we need to work with log(csoa) and log(it). Here we examine the analysis for log(it). We start with a model that is likely to be more complex than we need (it has all possible interactions):

tinting <- DAAG::tinting

itstar.lme<-lme(log(it)~tint*target*agegp*sex,

random=~1|id, data=tinting,method="ML")A reasonable guess is that first order interactions may be all we need, i.e.

it2.lme<-lme(log(it)~(tint+target+agegp+sex)^2,

random=~1|id, data=tinting,method="ML")Finally, there is the very simple model, allowing only for main effects:

it1.lme<-lme(log(it)~(tint+target+agegp+sex),

random=~1|id, data=tinting,method="ML")Note that all these models have been fitted by maximum likelihood. This allows the equivalent of an analysis of variance comparison.

Here is what we get:

anova(itstar.lme,it2.lme,it1.lme)

Model df AIC BIC logLik Test L.Ratio p-value

itstar.lme 1 26 8.146187 91.45036 21.926906

it2.lme 2 17 -3.742883 50.72523 18.871441 1 vs 2 6.11093 0.7288

it1.lme 3 8 1.138171 26.77022 7.430915 2 vs 3 22.88105 0.0065The model that limits attention to first order interactions appears adequate. As a preliminary to examining the first order interactions individually, we re-fit the model used for it2.lme, now with method="REML".

it2.reml<-update(it2.lme,method="REML")We now examine the estimated effects:

options(digits=3)

summary(it2.reml)$tTable

Value Std.Error DF t-value p-value

(Intercept) 3.61907 0.1301 145 27.817 5.30e-60

tint.L 0.16095 0.0442 145 3.638 3.81e-04

tint.Q 0.02096 0.0452 145 0.464 6.44e-01

targethicon -0.11807 0.0423 145 -2.789 5.99e-03

agegpolder 0.47121 0.2329 22 2.023 5.54e-02

sexm 0.08213 0.2329 22 0.353 7.28e-01

tint.L:targethicon -0.09193 0.0461 145 -1.996 4.78e-02

tint.Q:targethicon -0.00722 0.0482 145 -0.150 8.81e-01

tint.L:agegpolder 0.13075 0.0492 145 2.658 8.74e-03

tint.Q:agegpolder 0.06972 0.0520 145 1.341 1.82e-01

tint.L:sexm -0.09794 0.0492 145 -1.991 4.83e-02

tint.Q:sexm 0.00542 0.0520 145 0.104 9.17e-01

targethicon:agegpolder -0.13887 0.0584 145 -2.376 1.88e-02

targethicon:sexm 0.07785 0.0584 145 1.332 1.85e-01

agegpolder:sexm 0.33164 0.3261 22 1.017 3.20e-01Because tint is an ordered factor, polynomial contrasts are used.

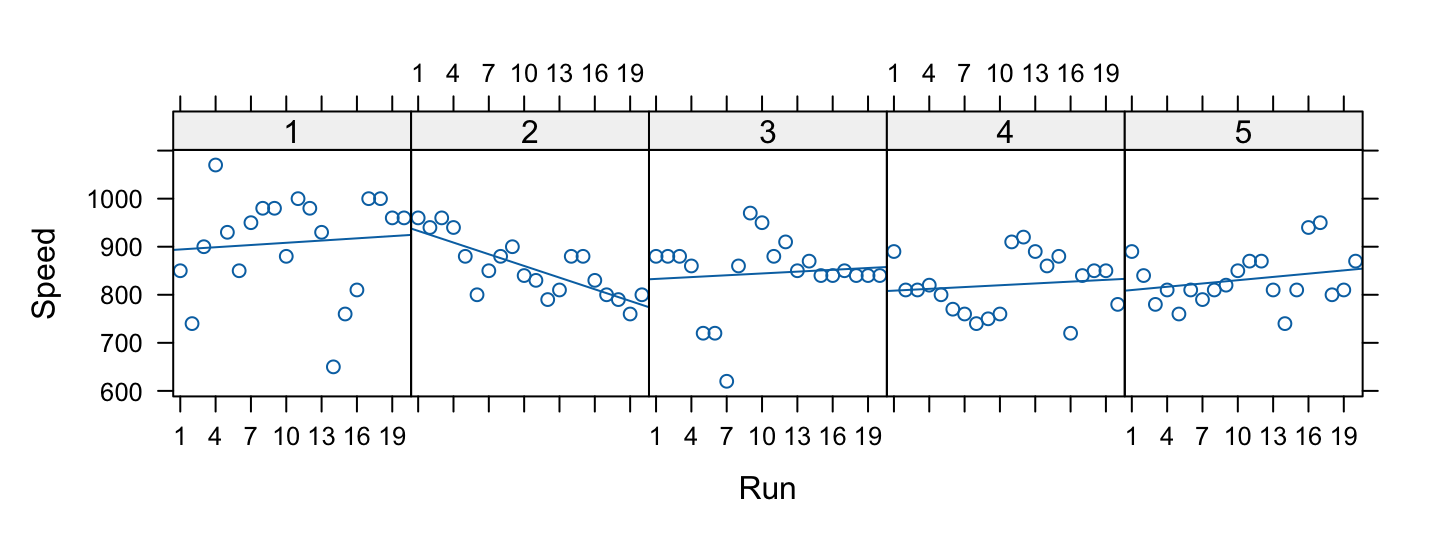

The Michelson Speed of Light Data

The MASS::michelson dataframe has columns Speed, Run, and Expt, for five experiments of 20 runs each. A plot of the data seems consistent with sequential dependence within runs, possibly with random variation between runs.

Code is:

michelson <- MASS::michelson

lattice::xyplot(Speed~Run|factor(Expt), layout=c(5,1),

data=michelson, type=c('p','r'),

scales=list(x=list(at=seq(from=1,to=19, by=3))))We try a model that allows the estimates to vary linearly with Run (from 1 to 20), with the slope varying randomly between experiments. We assume an autoregressive dependence structure of order 1. We allow the variance to change from one experiment to another.

To test whether this level of model complexity is justified statistically, one needs to compare models with and without these effects, setting method="ML" in each case, and compare the likelihoods.

michelson <- MASS::michelson

library(nlme)

michelson$Run <- as.numeric(michelson$Run) # Ensure Run is a variable

mich.lme1 <- lme(fixed = Speed ~ Run, data = michelson,

random = ~ Run| Expt, correlation = corAR1(form = ~ 1 | Expt),

weights = varIdent(form = ~ 1 | Expt), method='ML')

mich.lme0 <- lme(fixed = Speed ~ Run, data = michelson,

random = ~ 1| Expt, correlation = corAR1(form = ~ 1 | Expt),

weights = varIdent(form = ~ 1 | Expt), method='ML')

anova(mich.lme0, mich.lme1)

Model df AIC BIC logLik Test L.Ratio p-value

mich.lme0 1 9 1121 1144 -551

mich.lme1 2 11 1125 1153 -551 1 vs 2 2.63e-08 1The simpler model is preferred. Can it be simplified further?

8.2 References and reading

See the vignettes that accompany the lme4 package.

Maindonald and Braun (2010) . Data Analysis and Graphics Using R –- An Example-Based Approach. Cambridge University Press.

Maindonald, Braun, and Andrews (2024, forthcoming) . A Practical Guide to Data Analysis Using R. An Example-Based Approach. Cambridge University Press.

Pinheiro and Bates (2000) . Mixed effects models in S and S-PLUS. Springer.